My cousin, a real estate broker, just got a Tesla. There are plenty of reasons why he should feel good about it. A posh car improves his professional stance. He can conduct conference calls while driving to meetings. Also, according to public opinion, it might slow down climate change.

Another friend cancelled her plan of flying to Sri Lanka for a week of meditation, as the power bill for air conditioners surpassed the cost of an airplane ticket.

If you are reading this, this is no news to you. You might even consider changing your own behavior. Maybe you already have. I know I did.

I stopped eating Schnitzel for traditional Sunday brunches after my friend’s son reckoned the connection between agricultural production and greenhouse gas emissions. By shifting to corn patties, I tell myself I can keep challenging highway speed limits without feeling too bad for the environment.

Californian Highway © Egor Shitikov

But in the back of my head there is this lingering suspicion that personal actions will not suffice to turn the tide.

There must be a blind spot. We know that ignoring blind spots block the big picture. The media is not helping, as their drums bang to another tune.

The blind spot I am talking about is architecture and city planning.

The reason for overlooking the issue is quite simple. We are dealing with a complex matter. It would require us to think in decades rather than making plans for a weekend barbecue.

After all, we are only human. Instead of working out the challenge of sharing a draining pool of resources among billions of citizens, we prefer the instant gratification of a cone of ice cream.

A Blind Spot Called Architecture

The solution is simplicity. Let us break down complex issues in the most simple way possible.

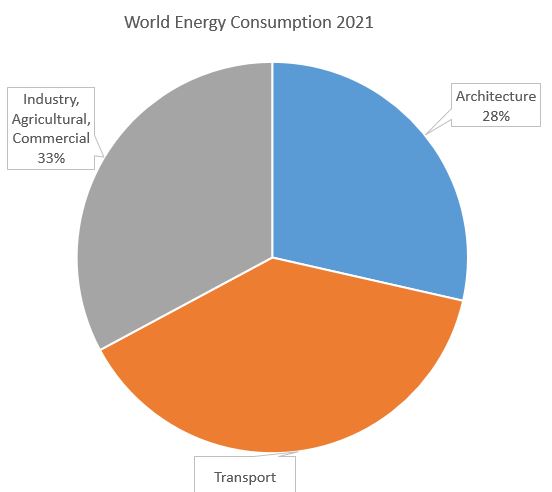

We broke up publicly available data for 2019 into three segments. 2019 feels more accurate as it discounts the covid disruption. We crunched numbers based on data published by the IEA, the International Energy Agency and similar reputable public sources.

The orange segment of the following diagram displays world energy consumption for transport except for transporting ores, building materials and other materials related to architectural and city planning. Any transport generated through unfavorable city planning is included in this sector.

The grey sector contains world energy usage for industry except for manufacturing building materials of steel, concrete etc. This sector also covers “Agricultural” and “Commercial” except commercial and agricultural architecture expenses, including heating, cooling and maintenance of such structures.

The blue segment shows the world’s energy use for architecture including construction, building and city maintenance, temperature control and all of the exceptions above.

What you see here is the blind spot. Architecture and affiliated activities makes up for almost a third of the world’s energy consumption.

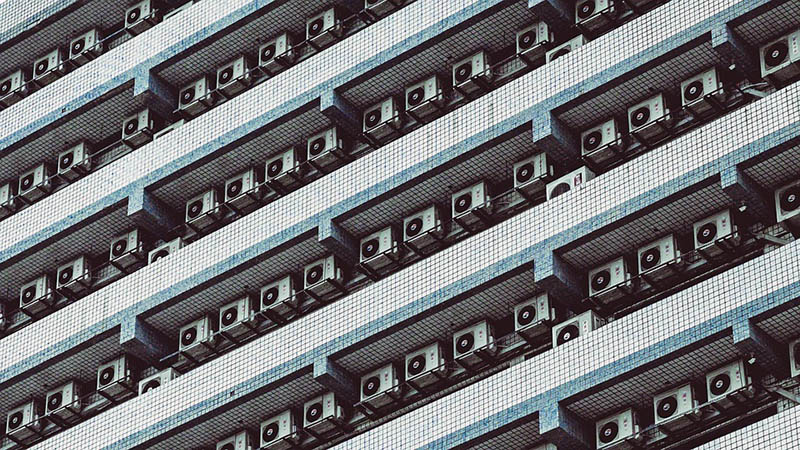

Within that sector, one of the biggest contributors is HVAC – heat, ventilation and air conditioning.

The use of air conditioners and electric fans accounts for nearly 16% of the total electricity in buildings around the world – or 10% of all global electricity consumption. Over the next three decades, the use of ACs is set to soar, becoming one of the top drivers of global electricity demand.

Studies predict that by 2050, roughly 25 percent of global warming will be caused by air conditioning.

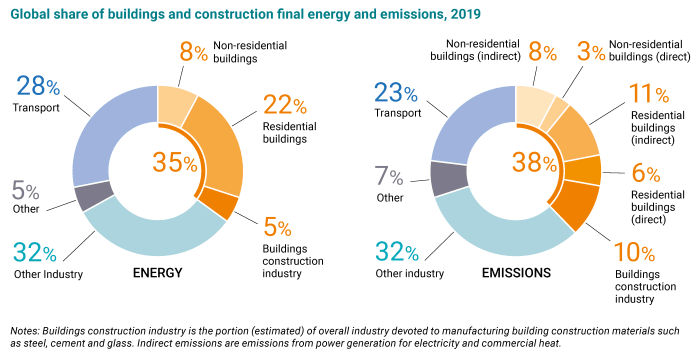

A diagram created by the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction, an UN environment programme shows a similar conclusion.

Carbon intensity and energy mix comparative data (source: UN Global ABC)

Please note, that we were not able to get accurate numbers on energy consumption on everything related to architecture and city planning. Should you dispute our results or have access to alternative sources that you deem more accurate – please do not hide behind your knowledge. Register, log in and write a comment. Even better, write an article for a good cause.

Good News and Bad News

When comparing consecutive data sets, air conditioning is the highest growing factor. With rising temperatures and firm believe in economic growth, we face a worldwide increase in demand for air conditioning.

Of course there is technical progress. Another set of data issued by the IEA shows that in the past 20 years things have improved. Take interior lightning as an example. Energy consumption for lightning per square unit decreased by 50% during that period, as LEDs improved incandescent lights. Heating is another example. Due to improvements in insulation and efficiency, energy consumption per square fell by 25%. It it were only for heating and illumination, architecture would not be a problem and offer a window for solutions at the same time.

Similar to illumination and heating systems, efficiency rates in cooling technology have improved in the last 20 years. It would be feasible to expect a modest reduction in energy consumption per square unit. However this is not the case. According to the IEA, energy consumption per square unit did not decrease at all. Energy consumption for cooling per square unit of building space increased by 25%. This is the same time period when heating and illumination went down significantly.

How is that possible? Sure, we already booked a slight increase in average temperature. But 0.18 degrees Celsius per decade are not enough to justify this boost of one quarter. Many more AC systems are up an running than 20 years ago and the number is ever increasing. This by itself is alarming. But it cannot be a reason. Many more buildings use AC than in the year 2000. The calculation covers that. The IEA calculated energy usage per square unit of building space. That means, the total amount of power consumption and and the number of AC’s humming away are irrelevant in this calculation. Despite improvements in technology the efficacy of cooling buildings has decreased. Methinks there must be another reason.

What If It Is Architecture Itself?

In the same 20 years, an ever increasing number of structures boasting with metal framed glass panels have been built. Many of them in hot regions where they are left to bake in the blazing sun. More than a few are fenced in with broiling highways. There is a chance that all this partakes in an increasing hunger for cooling. I want to raise a pressing question here. What if our lofty concept of post modernism is outdated?

After all, our idea of post modernism comes from a different era. Back in those times, architects gathered at cocktail parties with cigarettes in their hands. If they mentioned CO2 reduction at all, chances were this was not about climate change. It was likely to be about drinking less soda pops. When glittering towers were designed to adorn the headquarters of corporations, climate change was the going phrase to describe easing tensions between the Soviet empire and NATO.

At one point or another we will have to rephrase our idea of modernity. We might have to adopt a new set of esthetics that will be both beautiful and that will also contribute to moderating rising temperatures. These concepts will have to increase the quality of living. New concepts have only been successful when they improve everybody’s living standard. Reducing exploding energy bills are a start.

I have no doubt that ecological architecture will be a catalyst of a new modernity. We cannot wait for several overambitious carbon neutrality deadlines to pass and fail.

Ecological architecture means refurbishing existing buildings. It is about upgrading city centers. It will create alternative energy concepts for new commercial buildings as well as new homes. A reluctant shift from fossil energy to alternatives is not doing the job. A look at the diagrams reveals a blind spot. Without the introduction of ecological architecture, the ambitions for slowing down climate change are futile. We cannot ignore this sector. Its energy consumption is set to grow faster than all the other sectors combined.

Qbic’s mission is to shed light on the blind spot of architecture and city planning.

The Marita Schnepper Award aims to bring new ideas into the limelight. Concepts that may contribute to a positive change.